By Will Mavity

As part of its sweeping changes this year, the Academy has chosen to merge the categories of Best Sound Mixing and Best Sound Editing into a single category. Some Academy members had expressed dissatisfaction with the apparent inability of voters at large and viewing audiences to differentiate between the two categories. Indeed, it seems like every year someone asks, “What is sound editing?” One year, Morgan Freeman had to do a whole five-minute recap of the art during the category’s presentation to try and make the distinction clear to viewers. And, to be fair, in recent years, the distinction between the role of the sound re-recording mixer and the supervising sound editor has begun to blur more than it once did. Since Best Sound Editing expanded to a full five nominees in 2006, it has had the same winner as Best Sound Mixing eight times. Of course, the winners are selected by the entire Academy, not by the sound branch, and thus may not accurately represent that distinction. Additionally, AMPAS has been working to deliver a shorter show, and eliminating a category or two may have seemed like an easy way to do that.

This past season, Next Best Picture spoke with several members of the Academy’s sound branch after they received a December email floating the possibility of merging the two categories. At the time, those we spoke with were against the move. We’ve since spoken to several branch members who do approve of the merger, but the reactions overall seem mixed. Supervising Sound Editor Cecelia Hall (“The Hunt for Red October”) told us, “I thought it was kind of unfortunate that there was never any kind of public meeting about this. It’s not as if 100 supervising sound editors were invited to share their feelings on this. It was just the executive committee’s decision.” But what’s done is done. Before the category’s eulogy is read, and since this is likely the last time anyone will be asked, “what is the difference between sound editing and sound mixing,” this piece will try to describe what the sound editor’s craft has historically entailed.

Although the role has evolved considerably over the years, according to “The Beat”’s Logan Baker, “The sound editor is in charge of choosing the right sound effects, dialogue, ADR, foley effects, and music – as well as assembling all the pieces into the film’s final cut.” Oscar-winning sound editor, Mark Mangini (“Mad Max: Fury Road“) told “Variety,” “The sound editor creates the content that is captured by the sound mixer. It’s similar to a production designer creating content that is captured by the cinematographer.” As Oscar winner Ben Burtt once explained, excluding a few lines of dialogue and a footstep here and there, everything you hear in “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” from dialogue to breaths to the little squeaks of leather on Indiana Jones’ jacket, was created in post by the sound editors. [1] Meanwhile, Best Sound Mixing has honored the production sound mixer, who records on-set audio, and the re-recording mixer(s), who balance the levels of all of these individual sound effects along with re-recorded dialogue tracks and ambient noises.

As artist and filmmaker Adam McDaniel puts it: “Another misconception is that most of the dialogue and sound effects within a film have been captured by an ‘all hearing’ microphone during principal photography, capable of picking up every word, nuance, and noise with complete clarity. What they don’t realize is that most of a film’s sound – including much (if not most) of the dialogue – has been added long after the cameras have stopped rolling.” McDaniel discusses Disney’s “The Black Hole” and explains how it required “all the film’s dialogue to be re-recorded, due to a loud camera noise ruining the entire production track,” in a process known as ADR (automated dialogue replacement). For Hugh Hudson’s “Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes,” McDaniel notes how actress Andie McDowell couldn’t perfect the sophisticated English accent, and so, it was replaced with a voiceover by Glenn Close.

Of course, it’s not just the dialogue that sound editors have to recreate. It’s also everything you hear: doors closing, cloth ruffling, keys jingling – almost none of that comes from the original on-set take. And until the ‘90s, all of these sounds had to be cataloged in paper catalogs in a pre-digital era. That’s where you get some of the legendary stories of sonic experimentation that created the sounds you know and love: E.T.’s voice was created when sound editors merged the sounds of 18 different animals and people, including horses and Debra Winger [2]; The boulder in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” was a Honda station wagon on a gravel road [3]; The “Lord of the Rings” orc sounds were created by recording drunken rugby fans.

Why is this craft so important? As every film student knows, studies show time and time again that audiences may forgive middling cinematography, writing, and acting, but they won’t forgive bad sound. Cinema is nothing without its sound editors. George Lucas famously gave his sound team 50% of the credit for making his films work. Nine-time nominated sound editor, Wylie Stateman (“Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”), speaking to Next Best Picture, says: “The biggest problem sound has had over the years is that, as a line item, we represent 1.5 to 3 percent of a film’s budget, and yet people like Spielberg say that we’re 50 percent of the film experience. We’ve always punched way above our weight in value and anyone who’s ever worked professionally in sound knows that and has come to accept that.” People like Burtt probably decided what your childhood sounded like. And yet, they’ve had to fight year after year for recognition. Time and time again, the category was treated as a second-class citizen.

When presenting Sound Editing in 1999, Chris Rock stated: “I can say what I want up here. I mean, who am I gonna piss of? A foley artist?” Two years later, Mike Meyers opted to one-up Rock when introducing the Sounds saying: “Now, ladies and gentlemen, the award we’ve all been waiting for … Julia! OK. Sound and sound editing. Now, I know what you’re asking yourself. Will the winner this year be Chet Flippy or Tommy Blub-Blub or, perhaps, even Chad [unintelligible]. We don’t know, but what I do know is that what’s in this envelope is gonna send shock waves through the industry. Oh, yeah.”

In the early days of Oscar, the Sound Oscars would often go to the overall sound director at the studio that had released the winning film, even when that person had minimal involvement in the film while the people who had done the work were often ignored. Jimmy MacDonald, “The Dean of Sound,” who was responsible for all the sound effects for almost every Disney film until 1979 (and provided the voice of Mickey Mouse), never even had an official title at Disney. But without any on-set sound sources, those Disney animated films had to build all their sounds from scratch. For a while, MacDonald did it all himself as a one-man show using everything from cans full of dried beans to his own voice. In total, he provided Disney’s library with more than 28,000 sound effects. [4] Yet, he wasn’t even credited on the majority of Disney films, and certainly wasn’t ever nominated for an Oscar. When “Bambi” was nominated for Best Sound in 1942, Sam Slyfield, the overall Disney Sound Director was nominated, while MacDonald, who shuffled bamboo to create the sounds of forest fire in the film and otherwise made its world pop, was neither credited nor nominated.

In an attempt to rectify these constant oversights, sound editors started petitioning the Academy for their category as early as 1955. Finally, in 1963, the Academy introduced a category for “Sound Effects Editing”. The category honored “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” in its first year. By 1968, however, AMPAS decided to remove “Sound Effects Editing” as an annual competitive category. It did, however, leave the door open for the occasional Special Achievement Award in sound editing. Industry sound editors petitioned the Academy to reinstate the category in 1969, 1972, and 1973. Each time, their requests were rejected. Failing that, in 1974, Sound Editors proposed “Earthquake” and “The Towering Inferno” to the Academy governors for consideration for Special Achievement Awards in sound. Both films were denied recognition. The next year, Sound members recommended “Jaws” and “The Hindenburg”. The Academy governors refused to grant awards to both and only selected “The Hindenburg”. Finally, in 1977, the sounds of “Star Wars” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” were too innovative and overwhelming to ignore. Both requests for Special Achievement Awards were granted.

“Star Wars’” Burtt became the first “name-recognized” sound designer, getting profiles in “The New York Times” that detailed how he had spent two years collecting the sounds for R2-D2 and Darth Vader.[5] Yet, under the existing Oscar Sound category, he would not have been included as one of the nominees. A year later, they also granted a Special Achievement Award to “The Black Stallion”. Sound editor Richard L. Anderson (“Raiders of the Lost Ark”) tells Next Best Picture that Alan Splet, the supervisor of “Black Stallion,” was working in England on “The Elephant Man” at the time and had medical problems that made travel difficult for him to come to L.A., so he sent his regrets and didn’t attend Oscar night. I heard that the Academy Board was upset that they allowed a Special Achievement Award for sound editing that year, and Splet had the gall to not show up. Johnny Carson, the host of the 1980 Award Show, liked the sound of Splet’s last name and made jokes about him for the rest of the night, thus ensuring that the winner, who didn’t show, got more publicity than many who attended. As a result, Splet got a story about him in “People Magazine”.

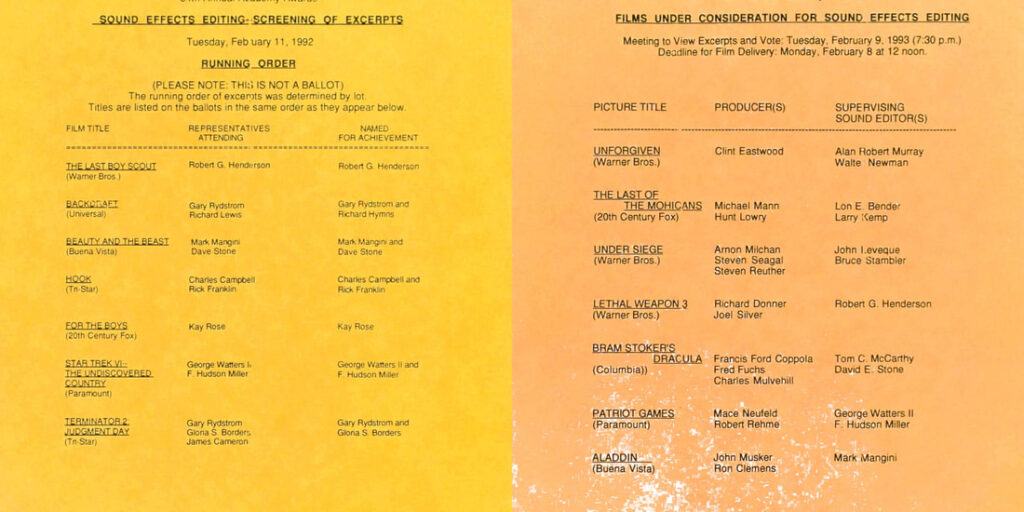

In 1981, the Academy finally reinstated Sound Editing as a category – the same year that the Academy debuted its Makeup category. Even then, the category was subjected to jeers. Jack Thomas of “The Boston Globe” wrote, “This year, for example, the Academy established another category…one more example of our compulsion to ensure that no American will pass unnoticed, unsung, or unrewarded.”[6] To select the category’s nominees, the Sound Editing and Makeup nominating committees adopted a practice from the Visual Effects branch that came to be known as “The Bake-Off”. Members of the respective academy branches would pre-select seven to 10 films as semifinalists. The technicians behind those selections were then asked to attend an event in January with the members of the Sound/Makeup/VFX branches present. At this presentation, they would screen 10-minute reels of their films, showcasing the relevant technical achievement. The technicians then answer questions from branch voters. Those voters rate the presentations on a scale of one to 10. Until the rules changed, films were required to receive an average score of at least 8.0 to be nominated. If no films met the necessary score, no award would be given. We saw this happen in 1983 with the “Best Makeup” category. If only one film met the 8.0 requirement or was so above and beyond its competitors, it would be awarded a Special Achievement Award. This occurred for Sound Editing in 1981 (“Raiders of the Lost Ark”), 1984 (“The River”), and 1987 (“RoboCop”). In David E. Stone and Vanessa Theme Ament’s case study, “Hollywood Sound Design and Moviesound Newsletter: A Case Study of the End of the Analog Age,” the authors explain that, in later years, voters were warned that too many years in a row of too few films with an 8.0 or above might lead the category to be returned to its occasional Special Achievement status of the ‘70s (pg. 101). Most years, however, at least two films met the score requirement and received nominations.

The Sound Editing category no longer uses bake-offs to select nominees. Instead, the term is mainly associated with the Visual Effects category, as the VFX bake-off not only continues to this day but is also now open to the public. However, in our interview with Anderson, he explains that the term bake-off started with Sound Editing. As he puts it: “I was the person who came up with the term ‘bake-off’. I know this sounds like every director working in Hollywood in 1929 who claims to have come up with the idea of putting the microphone on a stick (or boom), but this is for real. If the Academy had an official name for this event prior to my christening of it, I do not know what it was. As I recall, no one seemed to know what to call our yearly contest and it reminded me of the annual Pillsbury Bake-Off cooking contest, in that all the entries were different (a cake here, cookies there). So I jokingly called it ‘The Bake-Off’ amongst my friends and it seemed to have stuck with our band of sound artists – again because we did not have an official name. I see that the term was later transposed to the makeup and VFX categories also.”

The bake-off became a yearly highlight for many of the artists. In an interview with Next Best Picture, two-time winner, Alan Robert Murray (“American Sniper”), comments, “Those were good times. The bake-offs were loved by all.” The construction of these “bake-off” reels became an art unto itself. Several branch members said that some years, films with impressive sound kneecapped their nomination chances by presenting poorly constructed reels. Additionally, the order of presentation, determined by lottery, could make or break a film’s chances based on who the film was immediately next to. Three different branch members we spoke with mentioned Mangini’s speech when he was forced to introduce “Lethal Weapon 4” immediately following “Saving Private Ryan”’s overwhelming presentation. As Mangini tells us: “Knowing I didn’t have a chance, instead of introducing my film, I told a story about a famous juggling act, two Swedish jugglers in fact, who had the great misfortune to see their American television debut on February 9, 1964…the first public performance by the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show in the United States. Not only does no one remember their names, no one remembers that they even performed. In reviewing the kinescopes, it is amazing to see and hear crazed teenage girls still screaming and crying through the entirety of their performance. Understanding my fate, and having a good sense of a great sounding movie when I heard one, I exhorted my fellow Academy members to dispense with formalities and just give Gary Rydstrom the award right then and there.”

On the other hand, at least one voter believes that in 2005, the subtle work in “Memoirs of a Geisha” was nominated precisely because it was screened in the middle of more “obvious” reels of films like “Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith,” “The Chronicles of Narnia,” and “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.” Unlike most other categories, the category wasn’t deemed an official competitive category until 2004. Instead, it technically remained a Special Achievement Award given out year after year. As Mangini puts it, this was a yearly reminder as if to say, “Maybe there wasn’t anything really notable this year so we just won’t give an award at all”. He adds, “Can you imagine suggesting this concept to anyone such as the members of, oh, let’s pick an easy target, the Acting branch?” And, in fact, some years, the Academy gave the sound branch more than just “reminders.” According to Anderson, when “Raiders” was chosen by the sound branch for its Special Achievement Award in 1981, the Academy Board of Governors “decided to give the award at the Sci-Tech Awards ceremony, the weekend before the main Oscar show,” and adding: “I was disappointed that they chose to give our award during the Sci-Tech show, not for my personal glory’s sake, but because every other award that night was for designing technology (zoom lens development and Fuji film stocks). I felt that sound editing was an artistic award, like composing music, and not something technical. Ben [Burtt] and I each got a few seconds of TV screen time during the big show in the annual sportscaster-esque highlights of the Sci-Tech Awards (though we were invited to the big show and were run through the backstage press barrage during the middle of the event).”

In 1984, despite the presence of a massive contender like “Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom” or showy sounding sci-fi films like “2010” and “Dune” at the bake-off, Kay Rose blew voters away with her presentation of her work in “The River”. The sound branch was sufficiently impressed that they unanimously chose to award her a Special Achievement Award instead of submitting three finalists as Oscar nominees, just as they had with “Raiders of the Lost Ark” three years prior. Thus, Rose was about to become the first female Sound Editing winner in Oscar history. Upon submitting Rose’s Special Achievement Award to the Academy at large for approval, to their shock, the request was denied. The Academy’s explanation? Handing out a single award in a category would be “insufficiently competitive” and they wanted to cut the length of the show.[7] Although they had raised no qualms about giving “Return of the Jedi” a Special Achievement Award for Visual Effects in place of a competitive category the year before, apparently this time, offering this historic award was a bridge too far. Speaking with her daughter, Victoria Sampson, one academy governor said something along the lines of, “I don’t see what was so great about this. It’s just some birds and water and wind.” She also adds: “The Academy sound board that year felt that if [Rose] hadn’t gotten that Special Achievement Award, she might have never won an Oscar. It was a stellar sound job, but it was subtle. General academy members don’t vote for subtle sound movies. They think of good sound as explosions and musicals.” Rose preferred working on “quieter” films like “On Golden Pond,” “Paper Moon,” “Ordinary People,” and “The Prince of Tides”. Rose was a titan of the sound world. George Lucas once said he “grew up under [her] tutelage”.[8] This award was her one shot at winning an Oscar. As such, the sound branch protested so much that the Academy eventually capitulated and awarded Rose her Oscar. Oscar-nominated sound editor, Becky Sullivan (“Unbroken”), cited Rose’s win as a huge inspiration for her. USC ultimately created “The Kay Rose Chair in the Art of Sound and Dialogue Editing” through an endowment from Steven Spielberg and George Lucas.

In 2004, the rules were revised to require at least three films to be nominated, and the category officially became a competitive category instead of a special achievement award. In 2006, AMPAS revised its rules to remove the bake-off process, and instead, allowed the Sound Editing nominees to be selected the same way as most categories, with a full five nomination slots. That process has continued until this past year. The category’s bake-offs and final nominees demonstrated an openness to “non-Oscar” type films that are rarely evident in other categories. It provided an opportunity for female filmmakers to win Oscars in an era when gender representation was even more skewed than it is now. (It honored international films like “Das Boot”.) In David Lewis Yewdall’s “Practical Art of Motion Picture Sound,” he writes that one year, Finnish sound editor, Paul “Pappa” Jyrälä was selected for the bake-off despite coming from the small, international film “The Winter War” and competing for that slot against massive, showy blockbusters (pg. 95). The fact that he had been “painfully under-equipped and with too short a schedule for a picture of this magnitude” and still made incredible war sound effects impressed branch members.[9] Stateman recollects that “getting to go to the bake-off for a film that didn’t do big box office was always a great honor,” and, “it meant that the work in the film really spoke for itself. And the branch appreciated that.”

The bake-off also provided a tremendous variety of fun film anecdotes. Re-recording mixer, Kevin O’Connell, loves to talk about working on 2002 Sound Editing Winner “Pearl Harbor” for Michael Bay. He tells us: “Michael is the kind of guy who likes to let you know if you’re doing something right or wrong on sound or if he thinks it’s cool or not. And in ‘Pearl Harbor,’ they’re bringing planes up on an aircraft carrier elevator. And he wants it louder. And I’m like, ‘you want it louder?’ And he goes, ‘Yeah, I want it louder! Haven’t you ever been on a fuckin’ aircraft carrier? They’re really fuckin’ loud!’ So we redid the aircraft carrier elevator. The irony is that a couple of months later, we were at the world premiere of ‘Pearl Harbor,’ which actually took place in Pearl Harbor aboard an aircraft carrier, and my partner and I are standing on the aircraft elevator with Michael, and it’s silent. Like, it’s not making any sound at all. So we busted Michael’s balls about that and had a good laugh. And now there’s a running joke in our community about this. So, like, when we were working on ‘Hacksaw Ridge,’ we would go, ‘Haven’t you ever been fucking cooked with a flamethrower before? It’s really fucking loud!’”

Another favorite Sound anecdote we received (and we like to think it was a factor in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” demolishing its competition at the first-ever sound bake-off and securing a Special Achievement Award) was this all-timer from Mangini: “I was assigned to edit/design the sound fx in Reel 3 which contained the Raven bar fight. In it, Toht breaks a whiskey bottle on the bar and lights the contents on fire intending it to travel down the bar rapidly and incinerate Indy. We didn’t have the sound of fire “traveling” in our sound library so Richard [Anderson] and I decided to record it fresh on what was then the Ryder Sound Foley stage. This was a patently bad idea from the beginning as 1) no fire was allowed inside a studio of any kind, 2) we performed it in front of a standard Stewart cinema screen, wildly flammable, and 3) we did not arrange for a fire marshal to oversee the recording session. Richard and I began the recording session in one of the foley pits that was filled with sand (seemed the safest). Richard Rogers was recording in the booth while we worked out in the studio and Joan Rowe, the great foley artist, and Stephen Hunter Flick observed from afar. We opened a can of Sterno and lit it on fire as the source. Richard then squirted benzene from a squeeze can standing above me as I stirred the benzene into the Sterno, kneeling in the sandpit. Not getting the fire size or sizzle we wanted, Richard squeezed the can just a little too hard causing the fire to travel back up the thicker stream, up to his hands which were covered with benzene from squirting. This lit his hands of fire. Of course, his natural reaction was to drop the can. This had the unfortunate consequence of causing the can to catch on fire upon impact with the ground creating a large fireball as the lid popped off and benzene poured out. Instinctually, Richard attempted to “stomp” out the fire by stepping really hard on the can to extinguish it. This only caused the benzene liquid to splash all over his pants and travel up his lower body, lighting him on fire. We are rolling tape this whole time. Richard, now on fire from the waist down, does what any human might do: looks for water and jumps in what was supposed to be the foley stage “water pit” (every stage has one). Unfortunately for him, it was empty at the time. What makes this moment extraordinary is that Richard was not athletic in any way, but a man on fire can do amazing things including jump vertically practically three feet up and out of the empty water pit. We don’t know why (I’ve never asked him), but he then headed straight for the screen, and certain jail time for arson. The cool head in the group, Stephen had, in the meantime, grabbed a fire extinguisher and rushed to Richard and put him out. All of this takes no more than about 10 seconds but it felt like an eternity. And here’s what I love most about this story and Richard Anderson (who is now known throughout the sound community from this event as ‘The Incredible Burning Man’): though on fire, he never uttered a single word or sound. He knew we were rolling tape and he didn’t want to ruin the recording. That’s a pro.” Mangini later clarified that aside from melted pants, Anderson escaped unscathed.

The impression history gives off the sound branch is that of an amiable, good-hearted group of people who were less focused on the petty competition and squabbles of some other branches and more focused on seeing the work of their peers acknowledged. Multiple branch members fondly recalled the annual tradition of talking shop and catching up with old friends at the now-shuttered Kate Mantilini restaurant to talk shop before and after the presentation. Murray says: “I think the bake-offs, for those lucky enough to attend back then, will always be remembered as the greatest social event of the theatrical sound community. To vote, you had to attend and all pre-nominated highlight reels were run one after another in an incredible theater environment, exactly the way they were supposed to be represented. It was truly the best way of showcasing the craft of sound editing and sound mixing for the year!” According to Cecelia Hall, “What was great about the bake-off is a lot of us were working all the time, and didn’t have time to go see a lot of movies. Without the bake-off we would’ve been just voting for what we had actually seen that year. But here you would get to hear the best sound of the year showcased, including for movies you hadn’t had the chance to see yet. That’s why you had a lot of movies get nominated there that weren’t nominated for mixing, because people would just vote for what they had already seen that year in that category instead of getting to just really focus on the sound.”

The event was less of a competition and more of a class reunion. “Whenever I went to the bake-off, I wasn’t competing with the others. I was competing with myself and with science and subjectivity,” Stateman says. In his aforementioned book, sound editor, David Lewis Yewdall, once said of the event: “We were there not only to judge our colleagues but also to celebrate our art form and to be challenged throughout the coming year to raise our professional standards and artistic achievements accordingly,” (pg. 22).

Mangini still remembers when, in 1982, his partners, Anderson and Flick, were nominated for Sound Editing for “Poltergeist,” a film that the three of them co-supervised. “Our producer, Frank Marshall, had put Richard and Steve on the nomination form and that was what was accepted by the Academy,” he explains. “We were young and green back then and didn’t know that the rules only allowed two nominations for Sound Editing so, upon hearing the announcement of the nominations we were all surprised and a bit disappointed that I was left out. When I called Richard to ask if there was a way to get me on the nomination he replied that no, there wasn’t. The rules didn’t allow it, but that he would call the Academy and ask that his name be removed and mine added in his stead, adding that he had just won the year before for Raiders of the Lost Ark, and it was ‘my turn’. He wasn’t successful, but that act of generosity has stayed with me to this day. Who turns down an Academy Award nomination? Friendship!”

Most notable, the category was a haven for the unusual. It opened its arms to films that weren’t Oscar players elsewhere. Whereas Best Sound Mixing has generally catered to major overall Oscar contenders, especially Best Picture nominees like “The King’s Speech,” Sound Editing has provided a home for eclectic contenders. This was the category that brought us nominations for “Flatliners,” “Drive,” “RoboCop,” “All Is Lost,” “Wanted,” “Tron: Legacy,” “Fight Club,” and “The Ghost and the Darkness”. With the two categories merged, the nominees may be disproportionately the most “obvious” sounding films and the major Best Picture contenders overall. It seems unlikely that these smaller films will be recognized as much as they once were. In post-bake-off years, the Sound Editing category provided the sole nominations for “Tron: Legacy,” “Unstoppable,” “Drive,” “All Is Lost,” “The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies,” “Sully,” and “A Quiet Place”. What’s more, in the comparable BAFTA ceremony, which already honors winners with a single merged “Sound” category, only “All is Lost” and “A Quiet Place” still received nominations.

Under new rules, up to two supervising sound editors will still be nominated as part of the broader “Best Sound” category. But with only one category, unless Sound Editing was always going to have the same five films nominated as in Mixing, that likely means, statistically, fewer sound editors will be recognized each year. And those sound editors honored under this category may not be the sound editors whose work was most above-and-beyond in a given year. Anderson says, “In the past, sometimes musicals have won the Best Sound Mixing award. In many musicals, the sound effects editor doesn’t have much to do. If ‘Cats’ had won the new Best Sound category because people like the tunes, should the sound editor of that film get an Oscar? Nothing against him personally, but there wasn’t much besides music in that picture.”

If there’s any animosity between mixers and editors, however, even in light of this change, it seems minimal at best. As Stateman puts it, “The disputes and tensions between people in the sound branch was just a small glitch in the 100-year tradition of marrying sound to picture. For most of that time, there’s been artistry, and largely, that’s what we’re back to now.” Many in the branch are excited for the future of the category, and for the work that comes next. But let’s never forget the work that was required of artists of old to ensure that some of the most vital and hardworking people in Hollywood finally got even a sliver of the recognition they deserved. Now feels like the time to reflect on this piece of Oscar history. The lengths the sound editors went to for recognition, the opportunities they created, and the films that got Oscar’s attention through the category and its yearly bake-offs.

As such, here is a list of the Oscar Sound Editing semifinalists over the years. If a year has fewer than seven films listed, it means we were unable to confirm one or more of the remaining contenders. They had seven films every year between 1982 and 2005. Films that got their nominations are in bold while the eventual Oscar winner is marked with ***

1980

“Altered States” was submitted for a Special Achievement Award. According to Anderson, it contained “many weird design sound effects (which is why it was chosen), but the supervising sound editor, sound designer Steve Katz, and the composer all claimed to have created these sounds. Since the Oscar had to have names to go on the statue, the Board took the easy way out and dumped the award for that year.”

1981

“Dragonslayer”

“Heaven’s Gate”

***“Raiders of the Lost Ark”***

“Reds”

“Sharky’s Machine”

“Sphinx”

“Stripes”

“Superman II”

“Time Bandits”

“Wolfen”

1982

“The Dark Crystal”

“Das Boot”

***“E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial”***

“Poltergeist”

1983

“Blue Thunder”

“The Golden Seal”

“Never Cry Wolf”

“Return of the Jedi”

***“The Right Stuff”***

“Sudden Impact”

“War Games”

1984

“2010″

“Dune”

”Gremlins”

“Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom”

***“The River”***

1985

“American Flyers”

***“Back to the Future”***

“The Emerald Forest”

“Ladyhawke”

“Rambo: First Blood Part II”

“Runaway Train”

“Year of the Dragon”

1986

***“Aliens”***

“The Color of Money”

“Platoon”

“Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home”

“Tai-Pan”

“Top Gun”

1987

“Batteries Not Included”

“Cry Freedom”

“Full Metal Jacket”

“Lethal Weapon”

“Predator”

***“RoboCop”***

“The Witches of Eastwick”

1988

“Beetlejuice”

“Die Hard”

“Mississippi Burning“

***“Who Framed Roger Rabbit”***

“Willow”

1989

“Black Rain”

“Born on the Fourth of July”

“Glory”

***“Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade”***

“Lethal Weapon 2”

“The Winter War”

1990

“Dances with Wolves”

“Flatliners”

“Goodfellas”

***“The Hunt for Red October”***

“Total Recall”

1991

“Backdraft”

“Beauty and the Beast”

“For the Boys”

“Hook”

“The Last Boy Scout”

“Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country”

***“Terminator 2: Judgment Day”***

1992

“Aladdin”

***“Bram Stoker’s Dracula”***

“The Last of the Mohicans”

“Lethal Weapon 3”

“Patriot Games”

“Under Siege”

“Unforgiven”

1993

“Cliffhanger”

“The Fugitive”

“Geronimo: An American Legend”

***“Jurassic Park”***

1994

“Clear and Present Danger”

“Forrest Gump”

“The Shawshank Redemption”

***“Speed”***

“True Lies”

1995

“Apollo 13”

“Batman Forever”

***“Braveheart”***

“Crimson Tide”

“Heat”

“Under Siege 2: Dark Territory”

“Waterworld”

1996

“Daylight”

“Eraser”

***“The Ghost and the Darkness”***

“Independence Day”

“The Rock”

“Star Trek: First Contact”

“Twister”

1997

“Con Air”

“Face/Off”

“The Fifth Element”

“L.A. Confidential”

“The Lost World: Jurassic Park”

“Men in Black”

***“Titanic”***

1998

“Armageddon”

“Godzilla”

“Lethal Weapon 4”

“The Mask of Zorro”

“Ronin”

***“Saving Private Ryan”***

“The Thin Red Line”

1999

“Any Given Sunday”

“Fight Club”

“The Green Mile”

***“The Matrix”***

“The Mummy”

“Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace”

“Three Kings”

2000

“Cast Away”

“Gladiator”

“Mission: Impossible II”

“The Perfect Storm”

“Space Cowboys”

***“U-571”***

“Unbreakable”

2001

“A.I. Artificial Intelligence”

“Amélie”

“Black Hawk Down”

“The Fast and the Furious”

“The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”

“Monsters Inc”

***“Pearl Harbor”***

2002

“Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets”

***“The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers”***

“Minority Report”

“Road to Perdition”

“Spider-Man”

“We Were Soldiers”

“XxX”

2003

“Finding Nemo”

“Kill Bill Vol.1”

“The Last Samurai”

“The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King”

***“Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World”***

“Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl”

“Seabiscuit”

2004

“The Aviator”

“Collateral”

“The Day After Tomorrow”

***“The Incredibles”***

“The Polar Express”

“Ray”

“Spider-Man 2”

2005

“The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”

“Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire”

***“King Kong”***

“Memoirs of a Geisha”

“Walk the Line”

“War of the Worlds”

“Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith”

2006

“Apocalypto”

“Blood Diamond”

“Flags of Our Fathers”

***“Letters From Iwo Jima”***

“Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest”

2007

***“The Bourne Ultimatum”***

“No Country For Old Men”

“Ratatouille”

“There Will Be Blood”

“Transformers”

2008

***“The Dark Knight”***

“Iron Man”

“Slumdog Millionaire”

“Wall-E”

“Wanted”

2009

“Avatar”

***“The Hurt Locker”***

“Inglourious Basterds”

“Star Trek”

“Up”

2010

***“Inception”***

“Toy Story 3”

“Tron: Legacy”

“True Grit”

“Unstoppable”

2011

“Drive”

“The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo”

***“Hugo”***

“Transformers: Dark of the Moon”

“War Horse”

2012

“Argo”

“Django Unchained”

“Life of Pi”

***“Skyfall”***

***“Zero Dark Thirty”***

2013

“All is Lost”

“Captain Phillips”

***“Gravity”***

“The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug”

“Lone Survivor”

2014

***“American Sniper”***

“Birdman”

“The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies”

“Interstellar”

“Unbroken”

2015

***“Mad Max: Fury Road”***

“The Martian”

“The Revenant”

“Sicario”

“Star Wars: The Force Awakens”

2016

***“Arrival”***

“Deepwater Horizon”

“Hacksaw Ridge”

“La La Land”

“Sully”

2017

“Baby Driver”

“Blade Runner 2049”

***“Dunkirk”***

“The Shape of Water”

“Star Wars: The Last Jedi”

2018

“Black Panther”

***“Bohemian Rhapsody”***

“First Man”

“A Quiet Place”

“Roma”

2019

***“Ford v Ferrari”***

“Joker”

“1917”

“Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”

“Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker”

As a final note, we wanted to include a few anecdotes some of the category’s most recent winners shared with us about the films they won for:

John Warhurst on “Bohemian Rhapsody”:

“After attempting to layer up and create a stadium-sized crowd doing handclaps in time to the music to sound like a full stadium we decided the only way to do it would be to go to a Queen concert and ask Brian May to ask the audience to do single hand claps so we could record them and use this as the base of creating the Wembley Stadium crowd clapping along in time to the music. 20th Century Fox ran a marketing campaign called GetMeInBohemian.com where they invited people to sing along to Bohemian Rhapsody via an app. We were then given tens of thousands of recordings of people singing Bohemian Rhapsody, which we had to edit together and add to the Live Aid crowd for the finale of the film. We took Rami Malek’s recordings from on set and ADR and added beginnings and ends of words to Freddie Mercury’s vocal to make the performance feel more like Rami was really performing.”

Mark Mangini on “Mad Max: Fury Road”:

“On the last day of the mix, George Miller realized that Max had said something that didn’t make any sense. As he’s looking out over the great expanse of desert just before the final set-piece, he says to Furiosa, “it’s nothing but salt“. What George wanted him to say was “it’s nothing but sand“. We never had done ADR for this moment and it was a last-minute idea and we couldn’t get Tom Hardy. Fortunately for George, it was 9 AM and I hadn’t had my coffee yet. My voice can be quite gravelly in the morning. So I did the line, recording it on my iPhone in the backroom of the mix studio. That’s me in the final movie. My favorite sound in the movie is that strange-sounding “Waaa Waaa Waaa” bird call at the beginning of the film during Max’ voiceover. While seemingly heavily designed, this is actually an unprocessed recording of a real bird indigenous to Australia known as the Torresian crow; the animal kingdom’s saddest citizen, desperately in need of antidepressants. At the end of the film, when Nux sends the war rig into its death spiral, rather than using traditional crashes and booms, we used the sounds of dying animals to signify the death of a living thing, a character in the film. At the end of our mix-process, we played the entire film from beginning to end with the lights out. When the film finished and the lights came up, George stood to address the team and said ‘Mad Max’ is a film that we see with our ears. I had no idea that sound could help me tell this story so effectively.”

Special thanks to some of the sound greats who were invaluable in helping me research this piece:

Richard L. Anderson, Lon Bender, Larry Blake, Ben Burtt, Cece Hall, Mark Mangini, F. Hudson Miller, Alan Robert Murray, Kevin O’Connell, Don Rogers, Victoria Sampson, Wylie Stateman, David Stone, John Warhurst, Steve Williams.

Works cited:

- “Pictures: Science & Technology Get Own Honors Fete Ahead Of Oscarcade.” Variety (Archive: 1905-2000), 24 Feb. 1982, pp. 4–4, 40. Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive; Periodicals Index Online, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/1438366666?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Mancini, Marc. “Sound Thinking.” Film Comment, vol. 19, no. 6, 1983, pp. 40–43,45–47. Arts Premium Collection; Business Premium Collection; ProQuest Central; ProQuest One Academic; ProQuest One Literature, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/210246366?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Harmetz, By Aljean. “Space Sounds for ‘Empire’ Had Terrestrial Genesis.” New York Times (1923-Current File), 9 June 1980, p. 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times with Index, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/121234452?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Thomas, Jack. “TV & RADIO / BY JACK THOMAS; THE NIGHT TO INDULGE IN GLITTER AND TINSEL; ON TV: A POMPOUS PROGRAM WITH SOME TOUCHING MOMENTS: [FIRST Edition].” Boston Globe (Pre-1997 Fulltext), 31 Mar. 1982, p. 1. ProQuest Central; ProQuest One Academic, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/294181216?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- “Pictures: Sound Editors Present Pic Golden Reels To ‘River,’ ‘Heart,’ ‘Stone’.” Variety (Archive: 1905-2000), 27 Mar. 1985, pp. 4–4, 106. Entertainment Industry Magazine Archive; Periodicals Index Online, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/1438399218?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Blake, Larry. “George Lucas: Technology and the Art of Filmmaking.” Mix, Nov. 2004, pp. 88–94. Arts Premium Collection, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/1294196?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Yewdall, David Lewis. “‘Pappa’ Star of Talvisota Sound Crew.” American Cinematographer, Jan. 1990, pp. 66–68,70. Arts Premium Collection; ProQuest Central; ProQuest One Academic, libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy2.usc.edu/docview/196326687?accountid=14749. Accessed 12 May 2020.

We may not know what having one sound category looks like in 2020 but we will never forget the Best Sound Editing category and the winners it gave us over the years. What are some of your favorite wins? How do you feel about the two categories being combined? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section below or on our Twitter account.

You can follow Will and hear more of his thoughts on the Oscars and Film on Twitter at @mavericksmovies