“Spirituality is something that happens between a human being and the mystery of life.” – Paul Schrader

We all lead busy lives. Whether you’re a believer, an atheist, or a Buddhist monk, finding time to meditate on the mystery of our lives is hard to pencil in between a demanding job or a teeth cleaning. Cinema has always provided one avenue to soul-search and ruminate, with many of our greatest filmmakers––Bresson, Schrader, Bergman, Dreyer, Scorsese, Malick––as spiritual guides. Regardless of whether you believe in god, God or gods, the time of Holy Week––IE, the week on the Catholic calendar where Catholics reflect on Jesus’ death and later resurrection––is as good an excuse as any to look to how cinema has explored questions of faith, spirit and how to examine and live our lives. These are the seven movies that most abate my existential dread, giving me the comfort or provocation to ponder my place in what Schrader calls “the mystery of life.”

SILENCE (2016) Despite the popular misunderstanding Martin Scorsese is primarily a “crime movie filmmaker,” he’s stealthily been making movies about spiritual matters his entire career. These themes emerge in much of his work, most famously in “The Last Temptation of Christ,” but his 2016 masterpiece “Silence” has haunted me most. Wrestling with his own issues of faith and inviting viewers to do the same, “Silence” is as multifaceted and plural in meaning as any Scorsese has made. We follow two Jesuit priests (Adam Driver and Andrew Garfield) into 17th Century Japan, investigating the alleged apostasy of their religious mentor (Liam Neeson) into a country where Christianity is punished by drowning, crucifixions, and torture. “Silence” rivals “Goodfellas” or “Casino” in sheer brutality, but its real violence is of the spiritual kind, asking scathing questions on the limits of devotion, the ambiguities of the divine, and the cultural imperialism of missionary-imposed faith. Together, “Silence” and “The Irishman” represent a one-two punch of caustic reflection and unrelenting suffering, uncomfortable viewing experiences whose impact festers long after the credits have rolled. It’s one of Scorsese’s best.

Despite the popular misunderstanding Martin Scorsese is primarily a “crime movie filmmaker,” he’s stealthily been making movies about spiritual matters his entire career. These themes emerge in much of his work, most famously in “The Last Temptation of Christ,” but his 2016 masterpiece “Silence” has haunted me most. Wrestling with his own issues of faith and inviting viewers to do the same, “Silence” is as multifaceted and plural in meaning as any Scorsese has made. We follow two Jesuit priests (Adam Driver and Andrew Garfield) into 17th Century Japan, investigating the alleged apostasy of their religious mentor (Liam Neeson) into a country where Christianity is punished by drowning, crucifixions, and torture. “Silence” rivals “Goodfellas” or “Casino” in sheer brutality, but its real violence is of the spiritual kind, asking scathing questions on the limits of devotion, the ambiguities of the divine, and the cultural imperialism of missionary-imposed faith. Together, “Silence” and “The Irishman” represent a one-two punch of caustic reflection and unrelenting suffering, uncomfortable viewing experiences whose impact festers long after the credits have rolled. It’s one of Scorsese’s best.

THE TREE OF LIFE (2011) As much a prayer as a film, Terrance Malick’s metaphysical epic travels from the fraught domesticity of 1950s America to the celestial origins of our universe and possibly what comes after. Free-flowing, impressionistic, and humbly reaching for Heaven, Malick’s “The Tree of Life” juxtaposes fragments of his early life against an infinite cosmic scale. In one moment, a child is born, and the next, the birth of a planet. Later, a father’s feeling of helplessness turns love into fear and, ultimately, anger. He wants to protect his sons––he doesn’t know how. Elating to some and boring to others, I’ve learned to deeply love Malick’s masterpiece, the rare film to open new parts of myself and help me find new understandings of my parents and raising. But its most important lesson is how we should give ourselves permission to worship the splendor of our world and creation, regardless of where we choose to kneel.

As much a prayer as a film, Terrance Malick’s metaphysical epic travels from the fraught domesticity of 1950s America to the celestial origins of our universe and possibly what comes after. Free-flowing, impressionistic, and humbly reaching for Heaven, Malick’s “The Tree of Life” juxtaposes fragments of his early life against an infinite cosmic scale. In one moment, a child is born, and the next, the birth of a planet. Later, a father’s feeling of helplessness turns love into fear and, ultimately, anger. He wants to protect his sons––he doesn’t know how. Elating to some and boring to others, I’ve learned to deeply love Malick’s masterpiece, the rare film to open new parts of myself and help me find new understandings of my parents and raising. But its most important lesson is how we should give ourselves permission to worship the splendor of our world and creation, regardless of where we choose to kneel.

THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC (1928) Cinema’s ultimate expression of martyrdom, Carl Theodore Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” is to film what the Stations of the Cross are to any church. Told mostly through some of the most affecting and dramatic close-ups put to film, Dreyer guides us through a Christ-like sequence of trial, torture, and death, charged by Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s extraordinary performance. Through his masterful assembly use of close-up, editing, stark, high-contrast lighting, and minimalist set design, Dreyer performs the miracle of aligning Joan’s plight with the audience’s. Joan’s agony becomes our agony. Her ecstasy is our ecstasy. And, at least while watching, it’s as though her faith is now our faith. “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is a vital cautionary tale on religious persecution. Still, more importantly, Dreyer is the most successful filmmaker to ever place us inside the fervent mind of a steadfast believer.

Cinema’s ultimate expression of martyrdom, Carl Theodore Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” is to film what the Stations of the Cross are to any church. Told mostly through some of the most affecting and dramatic close-ups put to film, Dreyer guides us through a Christ-like sequence of trial, torture, and death, charged by Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s extraordinary performance. Through his masterful assembly use of close-up, editing, stark, high-contrast lighting, and minimalist set design, Dreyer performs the miracle of aligning Joan’s plight with the audience’s. Joan’s agony becomes our agony. Her ecstasy is our ecstasy. And, at least while watching, it’s as though her faith is now our faith. “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is a vital cautionary tale on religious persecution. Still, more importantly, Dreyer is the most successful filmmaker to ever place us inside the fervent mind of a steadfast believer.

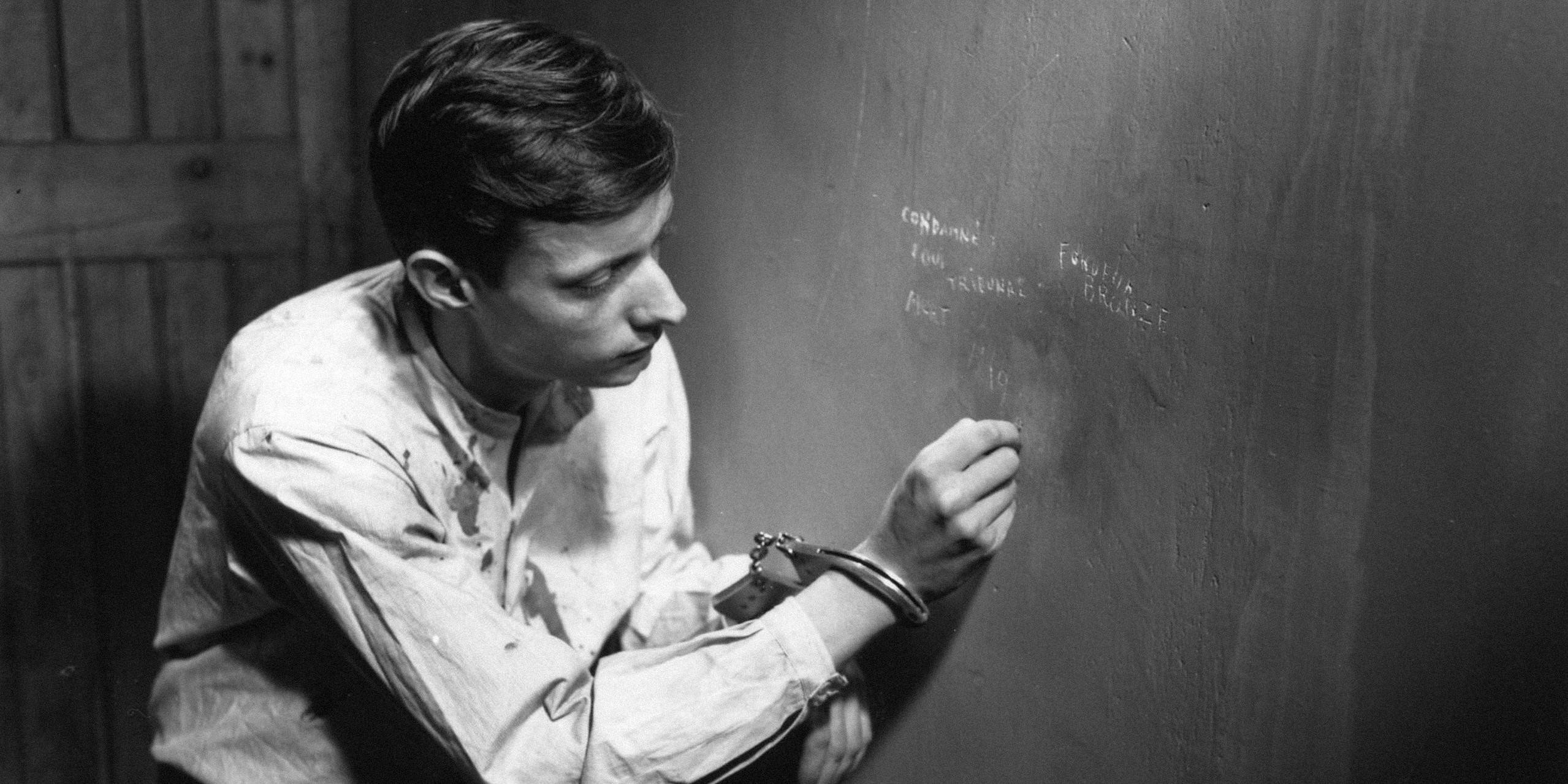

A MAN ESCAPED (1956) For me, spiritually, and the screen all starts with Robert Bresson. He is sometimes called “the Patron Saint of Cinema,” partly because of his prodigious mastery of the noir-infused craft with a sense of style as ascetic as his many struggling heroes. He recalls what Paul Schrader would lovingly label “transcendental style,” a cinematic language that abdicates the most emotionally charged tools of movie-making: the close-up, a heavy score, or flashy camera movements. Instead, it’s a style of sparseness and exclusion; Bresson demands the viewer to volunteer themselves into an experience that becomes closer to meditation than entertainment. However, this title is also earned for another reason. Like Scorsese, Bresson’s religiosity manifested in much of his work, sometimes overtly (“Diary of a Country Priest) and sometimes as subtext (“Au Hazard Balthazar”). For me, the power of Bresson is how he weaves the existential into the mundane and the soulful into the everyday. Through the careful arrangement of all cinematic elements, the simple tale of an imprisoned resistance fighter staging a break-out vibrates with the holy angst of a thousand pilgrimages.

For me, spiritually, and the screen all starts with Robert Bresson. He is sometimes called “the Patron Saint of Cinema,” partly because of his prodigious mastery of the noir-infused craft with a sense of style as ascetic as his many struggling heroes. He recalls what Paul Schrader would lovingly label “transcendental style,” a cinematic language that abdicates the most emotionally charged tools of movie-making: the close-up, a heavy score, or flashy camera movements. Instead, it’s a style of sparseness and exclusion; Bresson demands the viewer to volunteer themselves into an experience that becomes closer to meditation than entertainment. However, this title is also earned for another reason. Like Scorsese, Bresson’s religiosity manifested in much of his work, sometimes overtly (“Diary of a Country Priest) and sometimes as subtext (“Au Hazard Balthazar”). For me, the power of Bresson is how he weaves the existential into the mundane and the soulful into the everyday. Through the careful arrangement of all cinematic elements, the simple tale of an imprisoned resistance fighter staging a break-out vibrates with the holy angst of a thousand pilgrimages.

WINTER LIGHT (1963) If Bresson’s films are partly about a theological underlay to the currents of daily life, the charmingly gloomy Ingmar Bergman is the diametric opposite. Stark, depressing, and surprisingly funny, for Bergman, nothing is louder than the silence of God. A master at translating the philosophical query into the flow of conversation, “Winter Light” follows an aging pastor’s travels while his faith is challenged one parishioner at a time. Early on, a young man needs help. He is despairing about the atomic bomb. And the pastor, struck by his inability to give comforting counsel, concedes he’s also losing faith. He has his reasons, from the dwindling glow of feeling “chosen by God” to the “Problem of Evil,” identifying the atrocities of war as a parallel to Ivan’s heartbreak at the suffering of children in “The Brothers Karamazov.” A basis for Schrader’s “First Reformed,” “Winter Light” captures the pain––and the loneliness––of unrewarded faith with harrowing results.

If Bresson’s films are partly about a theological underlay to the currents of daily life, the charmingly gloomy Ingmar Bergman is the diametric opposite. Stark, depressing, and surprisingly funny, for Bergman, nothing is louder than the silence of God. A master at translating the philosophical query into the flow of conversation, “Winter Light” follows an aging pastor’s travels while his faith is challenged one parishioner at a time. Early on, a young man needs help. He is despairing about the atomic bomb. And the pastor, struck by his inability to give comforting counsel, concedes he’s also losing faith. He has his reasons, from the dwindling glow of feeling “chosen by God” to the “Problem of Evil,” identifying the atrocities of war as a parallel to Ivan’s heartbreak at the suffering of children in “The Brothers Karamazov.” A basis for Schrader’s “First Reformed,” “Winter Light” captures the pain––and the loneliness––of unrewarded faith with harrowing results.

FIRST REFORMED (2017) As if “Diary of a Country Priest” and “Winter Light” were channeled through the disturbed mind of Travis Bickle, in “First Reformed,” the writer of “Taxi Driver” pays his debts to create something feverishly his. Schrader builds upon the rock of the religion-set classics of his own church, one with a 21st Century flavor of existential anguish. No film before or since has better captured the bone-deep panic of Global Warming. As in “Winter Light,” a faith-wobbling pastor, here Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke), attempts to soothe the despair of someone in need. Rather than fear of nuclear armageddon, it’s a radical environmentalist with a bomb vest in the garage. He doesn’t want to bring a child into a world scientists say will most likely be uninhabitable. Toller’s descent into dread and consternation is terrifyingly relatable, contemplating how to keep his faith or maybe just his sanity when a planet, a people, and a God could so fully forsake our future. When asked what movie in the last decade has scared me the most, I always answer “First Reformed.”

As if “Diary of a Country Priest” and “Winter Light” were channeled through the disturbed mind of Travis Bickle, in “First Reformed,” the writer of “Taxi Driver” pays his debts to create something feverishly his. Schrader builds upon the rock of the religion-set classics of his own church, one with a 21st Century flavor of existential anguish. No film before or since has better captured the bone-deep panic of Global Warming. As in “Winter Light,” a faith-wobbling pastor, here Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke), attempts to soothe the despair of someone in need. Rather than fear of nuclear armageddon, it’s a radical environmentalist with a bomb vest in the garage. He doesn’t want to bring a child into a world scientists say will most likely be uninhabitable. Toller’s descent into dread and consternation is terrifyingly relatable, contemplating how to keep his faith or maybe just his sanity when a planet, a people, and a God could so fully forsake our future. When asked what movie in the last decade has scared me the most, I always answer “First Reformed.”

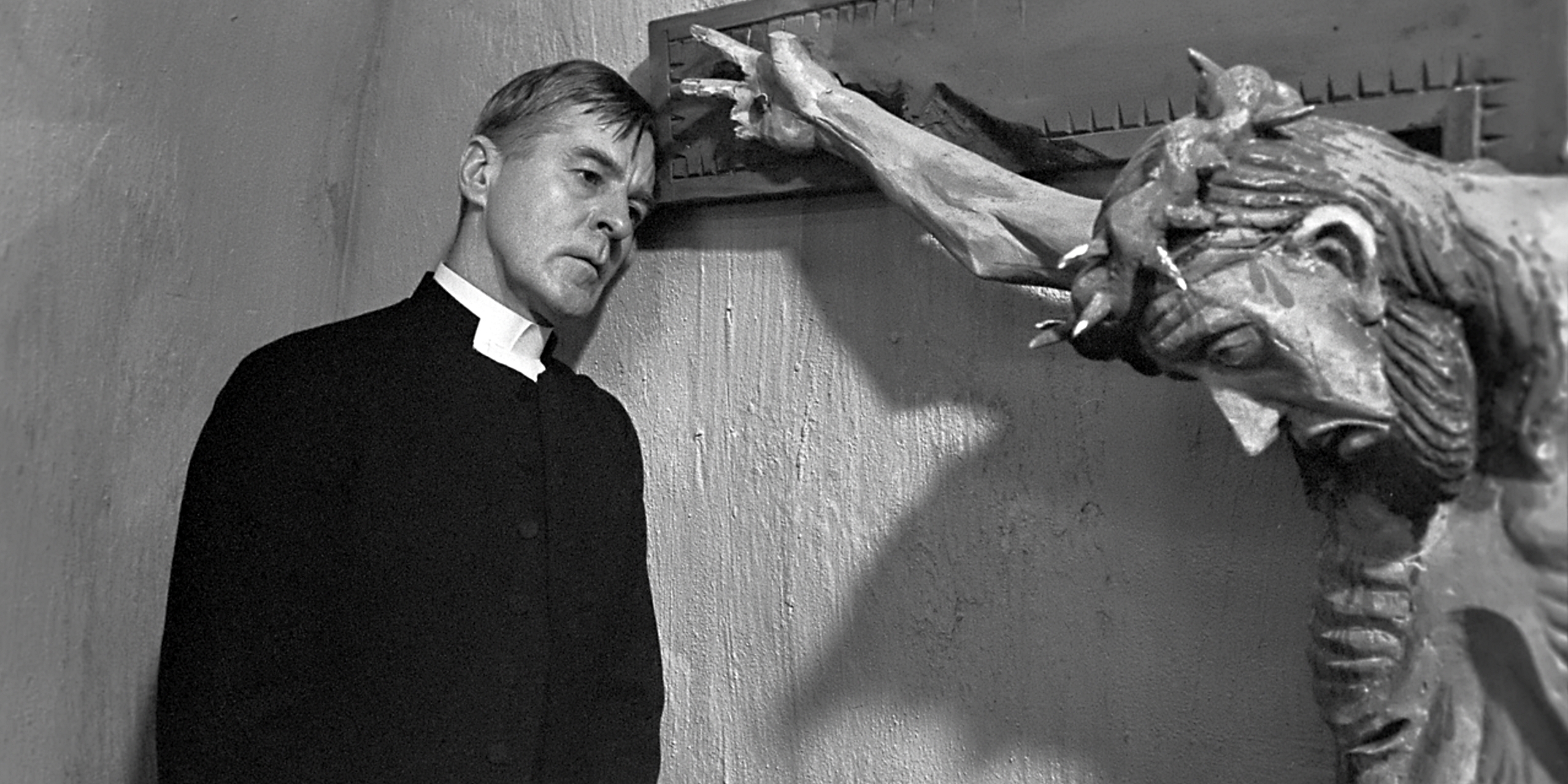

ORDET (1955) Where Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is the ultimate expression of religious persecution, his later feature “Ordet” is the ultimate depiction of religion as a dividing force. “Ordet” begins as a captivating dialectic between two preachers who, once friends, now hate each other. It later becomes something else. One sees faith as a mournful expression of an unforgiving world––what we must pay on Earth to be rewarded in Heaven. The other preaches a homily of joy and togetherness. We learn their children hope to marry, and we see the boundaries of denomination and doctrine tested with studied nuance as each preacher debates what should be done. I speak somewhat vaguely because “Ordet” is a film no person should want to spoil. Dreyer’s style, with “circular” camera patterns that gently bring the viewer into a drugged state of awareness, primes the audience for a shocking, forceful final act unlike any in cinema. Stop reading if you haven’t seen it, but “Ordet” takes a turn. Once it has, you will see no film has more definitively captured the seraphic ecstasy of divine might, inviting audiences of every faith, denomination, and doctrine to share religious bliss in cinema, if not in life.

Where Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is the ultimate expression of religious persecution, his later feature “Ordet” is the ultimate depiction of religion as a dividing force. “Ordet” begins as a captivating dialectic between two preachers who, once friends, now hate each other. It later becomes something else. One sees faith as a mournful expression of an unforgiving world––what we must pay on Earth to be rewarded in Heaven. The other preaches a homily of joy and togetherness. We learn their children hope to marry, and we see the boundaries of denomination and doctrine tested with studied nuance as each preacher debates what should be done. I speak somewhat vaguely because “Ordet” is a film no person should want to spoil. Dreyer’s style, with “circular” camera patterns that gently bring the viewer into a drugged state of awareness, primes the audience for a shocking, forceful final act unlike any in cinema. Stop reading if you haven’t seen it, but “Ordet” takes a turn. Once it has, you will see no film has more definitively captured the seraphic ecstasy of divine might, inviting audiences of every faith, denomination, and doctrine to share religious bliss in cinema, if not in life.

What do you think of our list? Do you have a favorite spiritual film you watch around this time of year? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments section below or on our Twitter account.