If every year is a great year for movies (at least, if you know where to look), it’s always a rewarding exercise to reflect on what each year’s body of work comes to represent. Throughlines and themes can seem to materialize out of the ether, with various subjects, ideas, or images repeated through makeshift groupings of films, whether by lucky coincidence or the idea that artists can be a lightning rod to capture the cultural electricity of a specific time and place.

The most obvious, of course, are “Barbie” and “Poor Things,” two pop-feminist movies about manufactured women experiencing bright and beautiful worlds, only to encounter the danger of men and patriarchal programming. They also share a vivid celebration of cinematic artifice in a way that’s all too rare. We experience eye-popping colors, bubblegum pinks, deep oranges, and Crayola crayon blues. The sets proudly look like sets and often foreground old-school matte paintings amidst ornate production design. Going back more than half a century for inspiration, Greta Gerwig and Yorgos Lanthimos lovingly borrow from Jacques Demy or German Expressionism while also sharing a clear love of Powell & Pressburger’s technicolor wonders. In a period when movies and T.V. are plagued with “realistic” lighting (read: all too often dim, unimaginative, and ugly), “Barbie” and “Poor Things” remind us of a time when movies could celebrate their stunning artificiality as worlds unto themselves.

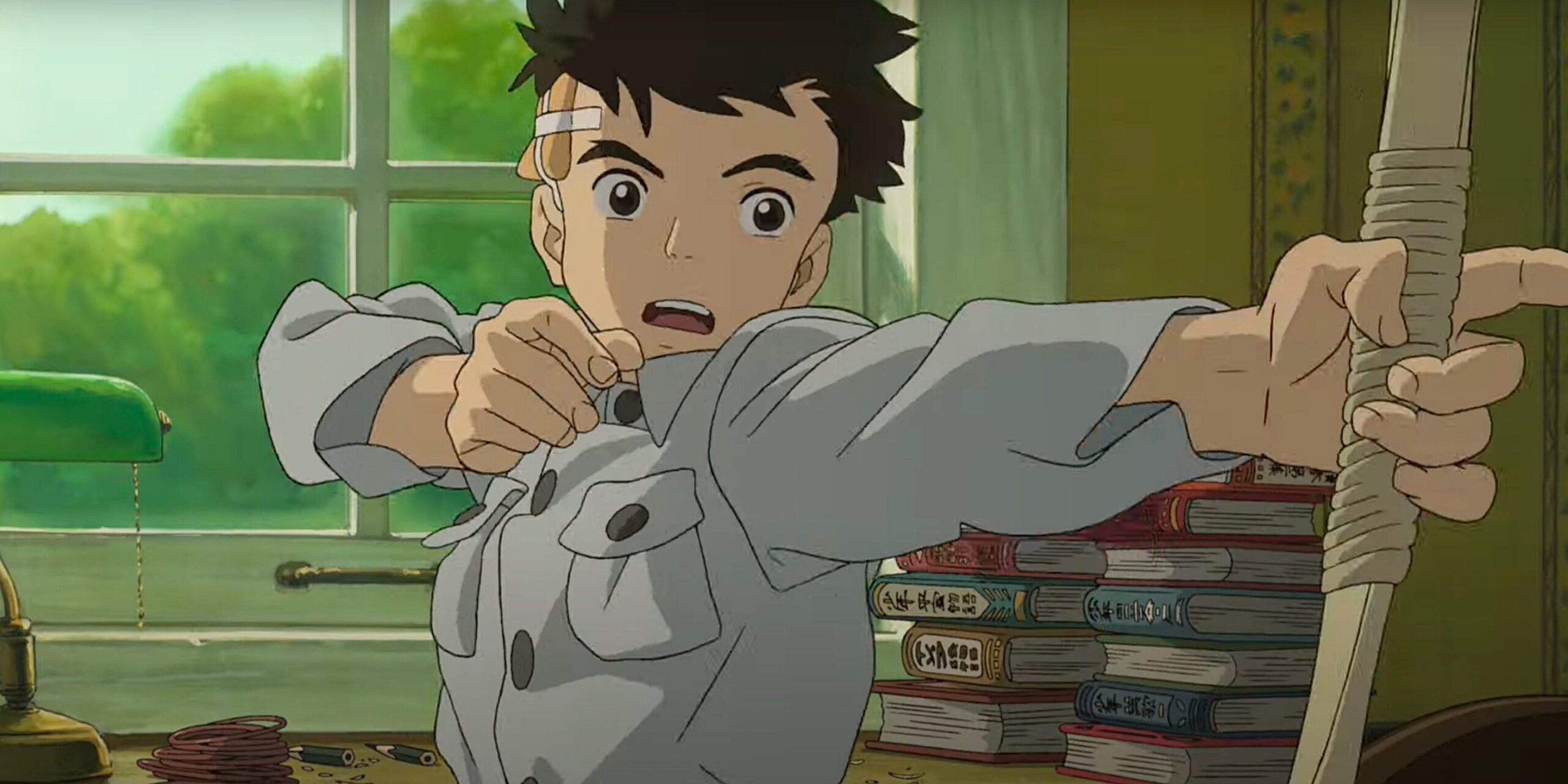

But mostly, this year, we had an unusually high number of movies musing on fascism, genocide, death, and dangerous men, the darkest of possible subjects, to reflect our increasingly grim concerns back at us. Often, this was through the lens of male directors ruminating on their careers and pushing old but depressing themes and motifs into new contexts. Schrader went towards the light with “Master Gardener,” while Scorsese went deeper into darkness in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” both about white supremacy past and present. Fincher recontextualized decades-old screeds of corporate dystopia from “Fight Club” into the surprisingly hopeful “The Killer,” and aging filmmakers (Hayao Miyazaki, Michael Mann, William Friedkin) who previously meditated on time’s cruel arrow made entire films devoted to the subject. And those themes of fascism, cultural oppression, and genocide run through everything from “Master Gardener” to “The Zone of Interest,” “Pacifiction,” “Oppenheimer,” and “The Boy and the Heron.” Plus, a run of “great men, shitty husbands” in “Oppenheimer,” “Ferrari,” and “Maestro.”

Even “Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One,” one of the most gleefully entertaining blockbusters of the year, presented an uncommonly morbid view of reality for an actioner. Ethan Hunt’s biggest threat wasn’t actually A.I. as many (including President Joe Biden) seem to think, but the danger of state power to overreach and how governments could use artificial intelligence to create new screens of reality by manipulating information to change our entire sense of “right and wrong” –– a harrowing Baudrillardian thought, given what’s happening in the Middle East, Ukraine, India, and back here in the U.S.

If much of 2023’s crop of movies suggested we are not okay and the world is walking backward towards disaster, all the more welcome were the balms for the soul: our popcorn movies. I felt the kinetic power of “breaking canon” and telling your own story in “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,” the swagger of ’60s-romp spy games and loony tunes set-pieces in “Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One,” or the classic Hong Kong action theme of loyalty and brotherly love in “John Wick: Chapter 4.” “Dungeons and Dragons: Honor Among Thieves” was the surprise delight of the year, which felt as though someone found it in a vault left in the mid-2000s when comedy wasn’t an apology for sincerity. Chris Pine sings as his face melts like someone left it in a high-powered microwave. And M. Night Shyamalan’s philosophical thriller “Knock at the Cabin” reminded us he’s one of the few filmmakers around to still show a camera’s framing, blocking, and movement can be the primary driver of a story.

As always, there is so much left to see. The omissions are huge. I didn’t get to the new Pretzold and Ceylan yet, even though I love those guys. I expect I’ll really love “All of Us Strangers” and “Showing Up,” and I want to give “Saltburn” a chance. My excuses are simple: despite being the third biggest city in the U.S., Chicago has a punishing release schedule. But mostly, it was just a busy year; my ever-demanding day job, along with some health worries, monopolized too much of my time, even as I wrote more than I had in the last eight years (something I’m proud of and extremely grateful to those who gave me the platform to achieve). I still saw plenty and loved many.

First, my (unranked) runner-ups: “Ferrari,” “The Caine Mutiny Court Martial,” “John Wick: Chapter 4,” “Knock at the Cabin,” “The Killer,” “Suzume,” “Dungeons and Dragons: Honor Among Thieves,” “Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One,” and “Godzilla: Minus One.” Here is my top ten of the year for 2023, which is nothing more and nothing less than a snapshot of movies that resonated with me most at the time I wrote up this list…

10a. Asteroid City

“I still don’t understand the play.

“I still don’t understand the play.

It doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.”

Wes Anderson’s “Asteroid City” plays almost as a full-length feature version of my favorite scene in David Lynch’s “Mulholland Drive.” Naomi Watts’ aspiring actress Betty auditions for a part in a B-grade jailbait soap, giving a performance-within-a-performance that breaks down the distinction between what’s “real” or not “real” and unleashes a geyser of surprising but authentic emotion; it doesn’t matter if “we” know we’re watching a “scene” in a movie, it moves us just the same.

Every other scene of “Asteroid City” follows that same kind of emotional logic, with a wonderfully ludicrous story-within-a-story concept only Anderson could dream up. We watch a staged program on television about the making of a fictional play that’s something like “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” meets “Looney Tunes,” full of cosmic ennui, nuclear foreboding, intense grief, and New York theatre. His predictably stacked company of stars are playing actors playing characters inside of other characters, with Anderson leaning into the artifice of his work as a way to show how emotion can transcend logic, order, or even narrative convention, all to convey the necessity of how art and storytelling nourish us in a world beyond our Earthly comprehension. Just keep telling the story.

10b. Master Gardener

“Gardening is a belief in the future. A belief that things will happen according to plan.”

“Gardening is a belief in the future. A belief that things will happen according to plan.”

Some inevitably found Paul Schrader’s latest the labored work of an aging provocateur stirring the cultural pot, contriving a plot where a reformed neo-nazi horticulturalist (Joel Edgerton) finds true love with the much younger half-white half-black grand-niece (Quintessa Swindell) of the garden’s owner (Sigourney Weaver). Sure, and viewed with the heightened dialogue, sparse visual style, and deliberate pacing –– I get it. Yet, when taken as the surprisingly sincere completion of a character arc begun in 1976 with “Taxi Driver,” where one of Schrader’s many “God’s Lonely Men” can finally find some kind of peace, the powerful seeds planted throughout his career begin to blossom anew. “Master Gardener” almost unfolds like a feature-length vision of the famous “What if” in Schrader’s own “The Last Temptation of Christ,” a beatific fantasy not necessarily of absolution but of radical acceptance and how hope can grow even in the most toxic soil. Aided by Edgerton and Swindell’s layered performances, I left deeply moved.

9. Poor Things

“I have adventured it and found nothing but sugar and violence.”

“I have adventured it and found nothing but sugar and violence.”

“Poor Things” is less an essay on feminist theory than an experiential tour-de-force through the eyes of a Frankenstein’d woman as she discovers her own agency, one pastry, shag, and mustached duplicitous male suitor at a time. Yorgos Lanthimos’ hysterical and furiously sex-positive adaptation of Alasdair Gray’s graphic novel takes us through a gorgeous Mary Shelly dreamland, at once cyberpunk, steampunk, and something of its own. Lanthimos might stretch his premise and repeat the same punchlines too often, but it’s the best film of the year to express what it’s like to have a body, to be flesh and bone, to have a brain in constant change. As a result, Emma Stone’s Bella Baxter rivals any motorcycle jumps and atom bombs in sheer cinematic spectacle, delivering a performance of bewitching and beautiful athleticism to master every new footstep, verbal intonation, or jerk of the shoulder, as she magnificently shows a mind in a state of nonstop metamorphosis.

8. The Holdovers

“You can’t even dream a whole dream, can you?”

“You can’t even dream a whole dream, can you?”

Cozy, melancholic, and healing all at once, Alexander Payne’s “The Holdovers” is small-cinema at its best, telling the story of a boozing curmudgeon classics teacher (Paul Giamatti) burdened with watching over ungrateful and, it turns out, deeply broken high schoolers over Christmas break. “The Holdovers” plays like a great undiscovered J.D. Salinger novel in the best way, with Dominic Sessa inhabiting a Holden Caulfield-adjacent delinquent who, like that struggling protagonist in Salinger’s most famous book, wields a thinly masked (but often very funny) facade that hides pains no child should bear. I loved how these characters are neither too smart or too dumb, too generous or too evil, too beautiful or too ugly. They felt real. I knew them. Payne patiently relates the study of history itself to how early life choices ripple into the future, ending with a grace note that it’s only in the shared acknowledgment of life’s difficulties that we might ever get past any of them.

7. Killers Of The Flower Moon

“The storm is powerful. So we have to be quiet for now.”

“The storm is powerful. So we have to be quiet for now.”

Completing Scorsese’s trilogy of spiritual and cultural distress that began with “Silence” and “The Irishman,” “Killers of the Flower Moon” is a brutal anti-western with the POV neither belonging to the masterminding outlaw nor the badged savior, but the banality of evil in human form: a dim-witted war veteran (Leonardo DiCaprio) who aids his Machiavellian uncle’s ethnic cleansing for cheap dollars and cents. Like other late-period Scorsese, “Killers of the Flower Moon” can be a punishing (and long) watch, withholding the genre trim of “Goodfellas” or “Casino” to depict our history of systemized genocide as pure but confrontational cinema. If there’s a flaw, it’s that Eric Roth and Scorsese’s co-written screenplay shows the growing pains transitioning from an FBI-lead whodunnit to unpacking the complex marriage between Ernest (DiCaprio) and Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladstone) –– they’re never quite sure how much to let us into Mollie’s head. Yet, Gladstone is so mesmerizingly great it barely matters, delivering a performance of such radiant pathos and startling humanity, her absence is felt as much, or more, than when she’s on screen. The final minutes will stand as one of Scorsese’s best and most daring endings, a moving acknowledgment of complicity in the horrors of the past and the narratives that erased them, and challenging his white audience to do the same.

6. Pacifiction

“Politics is like a nightclub. It’s a party with the devil.”

“Politics is like a nightclub. It’s a party with the devil.”

As if a John le Carré novel was left out in the sun and went slightly mad, Albert Serra’s “Pacifiction” is an unlikely marriage between the contemplative pace of a video gallery installation and a heat-stroked political thriller, musing on atomic terror, colonial angst and geopolitical fallout amidst peach-toned sunsets and twilight stakeouts for mysterious submarines. What begins with us following The High Commissioner (Benoît Magimel) as he cycles through his quotidian tasks of currying favor and influence over Tahiti, like negotiating the opening of a casino or threatening a worried priest, turns into a meditation on accepting obsolescence in the changing political tides around you. The glacial pacing surely won’t be for everyone, but it hit me like a vibes-heavy narcotic, delivering a hypnotic audio-visual experience unlike any this year.

5. Spider-Man: Across The Spider-Verse

“Everyone keeps telling me how my story is supposed to go. Nah. I’m-a do my own thing.”

“Everyone keeps telling me how my story is supposed to go. Nah. I’m-a do my own thing.”

The only choice for the sequel to the wildly acclaimed and already-maximalist “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” was to break the visual and narrative boundaries of what an animated movie –– maybe what any movie –– is supposed to look and feel like. With a thematically brazen Wachowskian plot that deconstructs the eternally recurring (superhero) canon and Miles’ place in it, the greatest achievement of “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” is how it blends, shifts, and remixes visual styles, not just scene to scene but shot to shot. Some knocked it for narrative messiness or being a “part one,” but for me, these are small quibbles next to the striking beauty of the mood-ring watercolors of Gwen’s reality or the comic-book splash panel mayhem of Miles’ home world and on it goes. The first time I saw “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse,” it felt like moving through an art museum on a speedrun, overloading my senses with character-amplified beauty. It’s a shot in the arm to the whithering superhero genre, a beacon to remind you what these movies are sometimes still able to be.

4. May December

“This is just what grown-ups do.”

“This is just what grown-ups do.”

With a plot that channels the identify-morph of Bergman’s “Persona” by way of gutter-rag dreck, Todd Haynes elegantly slips between lifetime-soap-camp, Sirkian melodrama, and ’80s neo-noir sleaze, crafting a rare gem as deviously fun as it is emotionally devesting. Haynes satirizes how we turn tragedy into content and commodify emotion while he unpacks layers of artificial identity as carefully applied as a face of makeup. Nearly nobody in “May December” is feeling just what they say they are, as Natalie Portman’s actress and Charles Melton’s victim share false fronts and uncertain trajectories; one seems to conceal an emptiness filled only through the twisted simulation of tabloid fantasy, the other unspoken wells of trauma. Ugly and beautiful all at once, Todd Haynes’ latest is a playful masterclass of tone and genre.

3. Past Lives

“If you leave something behind, you gain something too.”

“If you leave something behind, you gain something too.”

Some of my favorite films can locate the cosmic in the minuscule and intimate: Edward Yang’s “Yi Yi” or Terrance Malick’s “The Tree of Life,” foiling the lives of families contending with the small rhythms of life against our search for greater meaning. What’s remarkable about Celine Song’s debut, “Past Lives,” is that, at its best — it does just that. There’s a lot I love here: the beautiful 35mm cinematography, which is constantly framed to emphasize boundaries, liminal space, and transcience. There’s the way Song directs her performers: warm, nervous, and natural. But most of all, I loved how Song uses her real-life non-love triangle to build upon pragmatic adult understandings that defy obvious narrative resolutions –– “Past Lives” is neither too neat nor too messy, instead showing how life and love are something that happens to us as much, or more, than something we can control. Song uses shades of her own forked experience as a Korean immigrant to capture a multiverse of possibilities, revealing how the exits never taken are still living in the back of your head. But at some point, it’s time to say goodbye.

2. The Boy And The Heron

“Create a world without malice and full of beauty.”

“Create a world without malice and full of beauty.”

Hayao Miyazaki comes out of yet another fake retirement with a dazzling and dreamy confessional, projecting himself into a new adventure from the opposite ends of life: a troubled, grief-stricken youth and an old aging wizard who can’t seem to let his kingdom go. There’s more autobiographical detail in “The Boy and the Heron” than ever before, making it all the more revealing as Miyazaki’s darkest and most demanding film. This is Miyazaki looking back at his life and career and questioning, for himself most of all, what it all means as he returns to old designs, motifs, and themes: a love of things that grow, the animal pull to violence, a need to create, the fear of war and apocalypse, and the enduring salvation found in friendship and small things. If this is Miyazaki’s final film, it’s a stunning grace note to cap off one of the greatest and most triumphantly consistent careers in film history.

1. Oppenheimer

“These things are hard on your heart.”

“These things are hard on your heart.”

Half a year later, on the surface “Oppenheimer” still seems like an impossible achievement. It’s a near-billion-dollar drama for adults that summons all the sound and fury of Christopher Nolan’s cinematic toolbelt, leveraging IMAX-sized close-ups of Cillian Murphy’s face, Ludwig Göransson’s soaring strings, and a screenplay organized like a cubist jigsaw –– to warn us that our noblest intentions and smartest men will walk us towards self-destruction. It’s among the darkest films to break out to a wide audience, a collective of moviegoers who found solidarity in Oppenheimer’s guilt-addled mind and the tremulous awe of our impending apocalypse. But in retrospect, it does kind of all make sense. “Oppenheimer” is a sleek, brilliantly designed piece of popular filmmaking, a morally probing exercise in flawed subjectivity elevated to the urgency of blockbuster bombast. It’s the apotheosis of everything Nolan’s been building up to his entire career and an explicit sign that if you create intelligent, big-screen scale cinema, audiences will follow in millions.

What do you think of my list? Please let us know in the comments section below or on our Twitter account. Please check out Matt Neglia’s Top 10 Films Of 2023 here, Daniel Howat’s Top 10 here, Josh Parham’s Top 10 here and Tom O’Brien’s Top 10 here. The annual NBP Film Awards and the NBP Film Community Awards will come in a few days to allow you all some time to see those final 2023 awards season contenders and vote on what you thought was the best 2023 had to offer.