By Danilo Castro

Faith is an increasingly difficult thing to come by these days, and few directors have tackled it as honestly and consistently as Paul Schrader. For over 40 years, Schrader has made films about intense, isolated men who are broken down by their spiritual conflicts. Whether it be “Mishima: A Life In Four Chapters,” “Light Sleeper,” or his script for “The Last Temptation of Christ,” Schrader’s characters are haunted by a sense of guilt that reflects his strict religious upbringing. “First Reformed” acts as both rumination and a culmination to this career-long study.

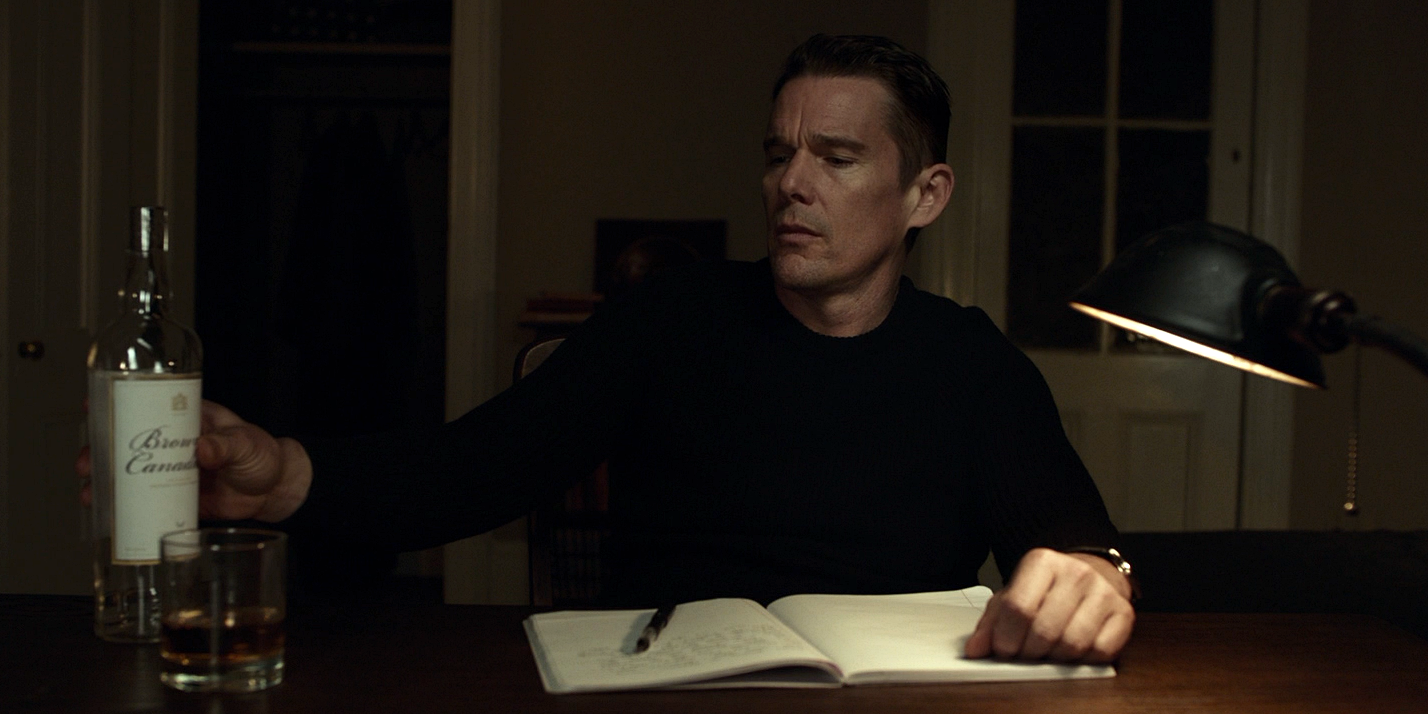

The film details the life of one Ernst Toller (An incredible Ethan Hawke); a reverend who, despite decades of service to the church, finds himself spiritually cut off from God. So desperate is he for something to believe in that he’s swayed by secular threats and set on a conflicting path that will force him to choose between personal desire and professional duty. Schrader and a career-best Hawke refuse to pull any punches along the way, presenting us with self-destruction that devastates largely due to how relatable Toller’s fears are.

“First Reformed” has rightfully been deemed one of 2018’s best releases, and yet, its Academy Award potential seems to have waned. It appears that the film’s critical support has, for whatever reason, been unable to translate to industry recognition.

Despite winning a handful of accolades from AFI, the Independent Spirit Awards and various online critic associations, the film was completely overlooked by the Golden Globes and the SAG Awards. It also failed to receive a PGA or single BAFTA nomination. All of these precursor nominees are typically the ones that lead to a Best Picture nomination, or even the Best Actor and Best Original Screenplay noms that the film was originally predicted to land, but Schrader’s searing character study appears to be losing steam when it needs it most.

With A24 failing to provide a campaign for the film, I implore the Academy to reconsider “First Reformed” as voting comes to an end. The aspects that make the film discomforting and at times troubling to watch are the very same elements that make it an essential release for 2018. We live in a time that is morally sullied and difficult to navigate, where answers don’t always come easy. Toller’s search for purpose after a lifetime of servitude is similarly difficult. However, you wish to describe his ordeal– midlife crisis, mental breakdown, spiritual breakthrough– it’s easy to relate to his sense of futility amidst bigger social issues.

As Toller, Hawke gives an austere, Oscar-caliber performance. The humor and charisma he usually brings to the table are swapped out with a litany of fake smiles and a melancholy that he can barely repress around others. It is only when he interacts with Mary (Amanda Seyfried), a pregnant widow, that the constraints on his spirit loosen and he is allowed genuine moments of happiness. It’s here that we catch glimpses of what he may have been like before he lost his way. Toller may be the most somber and tragically written of Schrader’s characters, but it’s Hawke’s natural warmth that truly sells him. By playing against type, the actor forces us to confront the traumas that changed him so radically.

Schrader’s screenplay is the film’s other Oscar-worthy component. While the premise and the main character are comparable to his earlier films, “First Reformed” stands out because of his willingness to tackle his obsessions directly. He’s no longer diffusing his characters with sexy neo-noir lighting or surreal environments (“Mishima”), he’s telling a story about a man who lives in our current world, and whose crisis of faith is ugly and intimate. It is all the more powerful as a result.

Schrader’s ambiguity is another aspect that strengthens the screenplay. Where so many of 2018’s critical darlings arrived with a clear agenda in tow, “First Reformed” purposely muddies the waters. We see Toller align himself with progressive causes, and make noble choices, but we also see him skew the other direction and make morally objectionable choices. We see him act tenderly towards Mary and unforgivably towards Esther (Victoria Hill), with whom he previously had an affair. Even in the film’s last scene, Schrader leaves it to us to decide whether Toller gets saved or gives in to his despair.

Furthermore, because the Academy Awards are a tradition that thrives on narrative, I would like to remind voters that Schrader has never been nominated for an Oscar. The man who has written such classics as “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull” doesn’t have a single nomination of his own. This would be a rare instance of a legendary filmmaker getting his due while competing with a film that’s just as good as any of its peers. It may be a Hail Mary at this point but I humbly ask, that you please consider it.

You can follow Danilo and hear more of his thoughts on the Oscars and Film on Twitter at @DaniloSCastro