An artist residency at golden hour, a city park thick with trees, and an amber-lit nighttime bar are a few of the carefully chosen locations featured by Celine Song in her twinkling debut “Past Lives,” which uses place, image, and sound to gently capture profound revelations about the lives we live and some of the lives we didn’t. Song uncovers these revelations through her own life as a Korean immigrant who fell in love across continents and decades and reunited with a childhood sweetheart after she was married to someone else. From the deceptively “smallest” of stories, Song effortlessly bottles, as though she’s catching lightning, how life can be transient but connected, chanced and fated, ephemeral yet everlasting. To try and do justice to all Song has to say, and how elegantly she can say it, turns casual chatter into half-conjured prose and lyricism. “Past Lives” inspires the lyrical and the lofty; to describe it in ordinary or casual terms seems impossible. But while we try, perhaps clumsily, to express all “Past Lives” offers us through our words, Song’s done it through the tools of cinema, finding a visual language of connection and reconnection through the in-between and liminal spaces surrounding our lives.

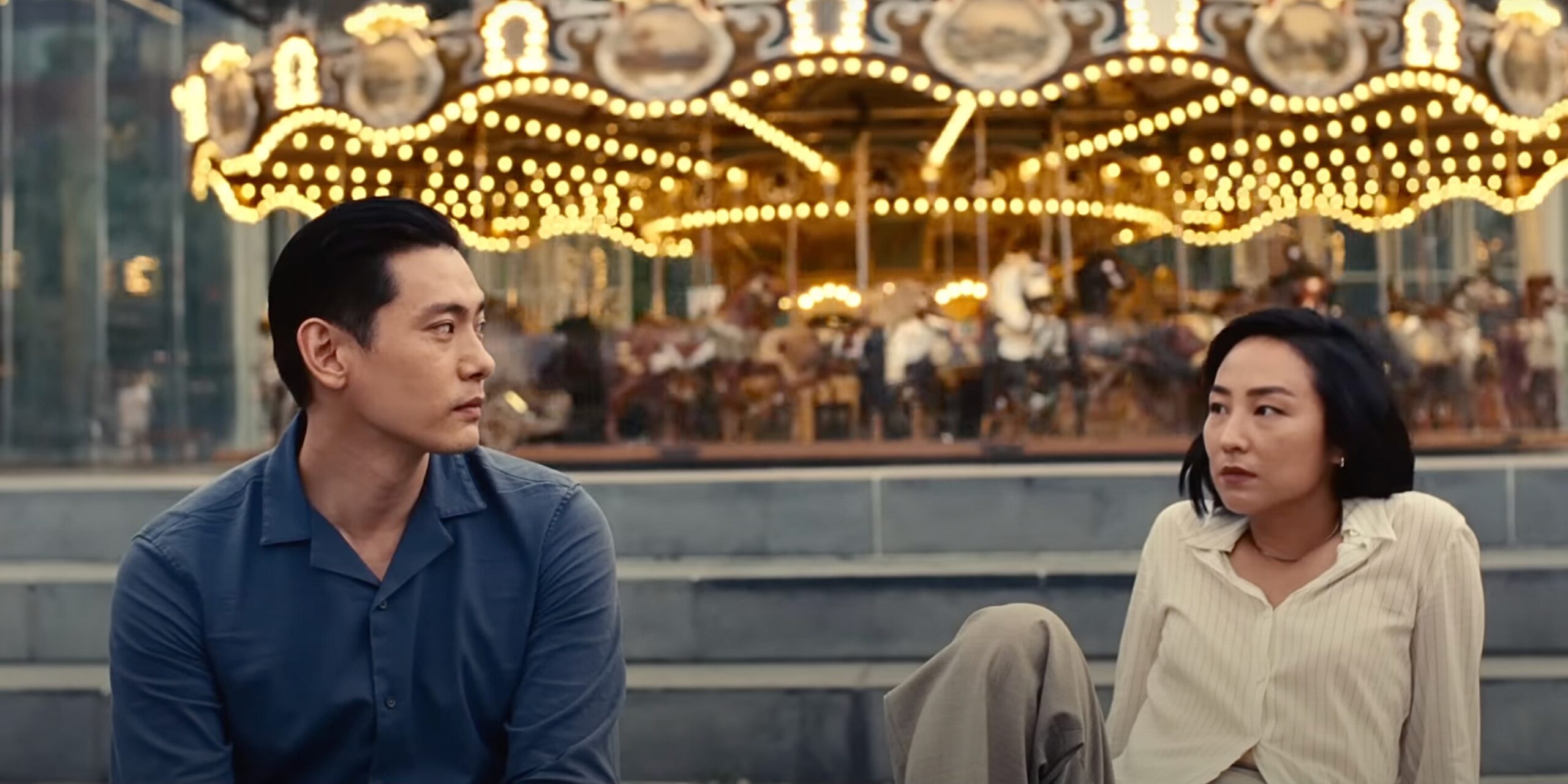

Celine Song is no stranger to how the specifics of a story’s environment can radically reshape how we feel about the way it’s told. In 2020, Song, originally a playwright, updated Chekhov’s classic “The Seagull” through the virtual proscenium of “The Sims 4.” The performance was streamed on Twitch with a voice cast, and Song not only replied to the live commenters watching in, but she let them influence the show. It was a unique achievement in multimedia storytelling, revealing an artist with a keen sense of how form influences how we engage with stories. Video games are an interactive medium, and film isn’t. Still, that same ethos is infused in every moment of “Past Lives,” which, like the visual storytelling of Wong Kar-wai, Kogonada, or Bernardo Bertolucci, curates the geography of urban architecture as a metaphor for internalized human feeling. Song’s surrogate is Nora (Greta Lee), a playwright whom we first meet in a bar (the first of Song’s thoughtfully chosen spaces) at a distance with two men beside her and soon after as a child up close. Like Todd Field’s “Tar,” the introductory minutes of “Past Lives” follow an unknown character, another patron at the bar, speculating who this unlikely trio is at this bar past midnight and what they might mean to each other. “They” are Nora, her first crush Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), and her husband Arthur (John Magaro), facts Song initially keeps from us. For now, they are an inaccessible tableau of two Koreans who seem like lovers and a white guy who sits next to them but is somehow miles away. The unnamed speaker makes guesses (all wrong), trying to piece together new combinations that may explain this odd apparent throuple. Song’s prologue is a trick of point of view and a lesson in context. Initially, Arthur seems like a forgotten third wheel, but by the end, it’s clear his silence is an act of spousal trust, a discovery earned slowly as Song lets the intricate narrative threads of her story unspool.

Song’s surrogate is Nora (Greta Lee), a playwright whom we first meet in a bar (the first of Song’s thoughtfully chosen spaces) at a distance with two men beside her and soon after as a child up close. Like Todd Field’s “Tar,” the introductory minutes of “Past Lives” follow an unknown character, another patron at the bar, speculating who this unlikely trio is at this bar past midnight and what they might mean to each other. “They” are Nora, her first crush Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), and her husband Arthur (John Magaro), facts Song initially keeps from us. For now, they are an inaccessible tableau of two Koreans who seem like lovers and a white guy who sits next to them but is somehow miles away. The unnamed speaker makes guesses (all wrong), trying to piece together new combinations that may explain this odd apparent throuple. Song’s prologue is a trick of point of view and a lesson in context. Initially, Arthur seems like a forgotten third wheel, but by the end, it’s clear his silence is an act of spousal trust, a discovery earned slowly as Song lets the intricate narrative threads of her story unspool.

An almost empty late-night bar is a perfect first venue for Song’s purposes because, like nearly every location in “Past Lives,” it has the quality of the liminal. It is a place that is both public and private, with invisible walls that separate groups and couples, transparent boundaries that allow voyeurs from without, and intimacy within. Like most of the arousing backdrops featured across the film’s multiple cities and continents, it’s a place you’re eventually expected to leave. Dear few scenes in “Past Lives” take place inside the rooted nest of a home or apartment, where things can grow and last, able to be nurtured. Instead, the drama is set almost entirely in locations that imply transit, loss, or change: boats, trains, airports, parks, libraries, hotels, sky trams, and many car rides. The handful of scenes that do take place in a home welcomes the liminal like an invasive force; Nora’s first reconnection with Hae Sung since childhood is filtered through unstable, low-bandwidth video, emphasizing how fleeting their new bond truly is. Further, when we meet Nora as a child, it’s another place between places, under a canopy of electrical wires as she and Hae Sung walk home from school. When they first hold hands, it’s in the backseat of a car in motion. Nora’s Korean name is Na Young, and when she’s asked to choose a new one (Nora Moon), her parents are already packing to leave. When we first meet Nora and Arthur as a married couple, it’s not in the warm domain of their Brooklyn flat but in an airport terminal — another of “Past Lives‘” many arrivals and departures. Similarly, we can look at how Song quietly dwells on the train cars and ferries as Nora and Hae Sung ride them, traveling to a final destination of a park overlooking a panorama of bridges and boats — a living map of a population in phases of crossing.

Further, when we meet Nora as a child, it’s another place between places, under a canopy of electrical wires as she and Hae Sung walk home from school. When they first hold hands, it’s in the backseat of a car in motion. Nora’s Korean name is Na Young, and when she’s asked to choose a new one (Nora Moon), her parents are already packing to leave. When we first meet Nora and Arthur as a married couple, it’s not in the warm domain of their Brooklyn flat but in an airport terminal — another of “Past Lives‘” many arrivals and departures. Similarly, we can look at how Song quietly dwells on the train cars and ferries as Nora and Hae Sung ride them, traveling to a final destination of a park overlooking a panorama of bridges and boats — a living map of a population in phases of crossing.

These locations bear the markers of passing and transference, emotional and physical, asking us and her characters what we can leave behind and what we can’t. It’s a question of where we move, how our goals evolve, and how our agency influences how some relationships blossom and others whither. Which parts of our identity can we let shift? These are universal questions, explored through Song’s specific lens, unpacking the immigrant experience in equally liminal terms as an airport terminal or Shanghai hotel room. Caught between cultures, after Nora and Hae Sung’s first outing as adults, Nora confesses she feels less but also more Korean when she’s with him, the paradox of a diasporic identity she’s still trying to process. “He’s so Korean,” she says, reminding her of a culture she feels once belonged to her and no longer fully does. When Nora’s mom is asked why the family is moving abroad, she answers: “If you leave something behind, you gain something too.” This is the film’s thesis statement, but it could be a trying platitude. Song treats it as both, acknowledging the honest messiness and emotional complexity that comes from being between places, between romances, and between identities. There’s the old axiom: the more specific the story, the more universal it feels. “Past Lives” proves it true. Eventually, Song lets us get to know Nora, Hae Sung, and Arthur, but on her terms and in her way. Like the transparent boundaries she creates around her characters, she has boundaries too, some figurative but many literal. She decides how close we’re allowed to get to Nora and, by extension, herself, alternating traditional close-ups with compositions that distance us. Song constantly uses frames within frames, characters positioned inside doorways, train windows, house windows, car windows, hotel windows, phone windows, and computer windows. When we see Nora and Hae Sung’s hands holding a metal beam on a train for support, their hands are nearly overlapping, almost primed to consummate their meeting with an extramarital holding of hands. We see it through another train car’s window; we meet Arthur for the first time through the window of an artist residency. When Hae Sung asks Nora to visit him in Seoul, and they mutually realize it won’t work, the camera rests on a window looking outside as day turns to night, setting the sun on their hopes for a relationship. Inside Nora and Athur’s apartment, Song sometimes frames their bedroom cuddles and pillow talk through the door’s wide windows, returning us to the point of view of the opening scene — as a voyeur, a guest in these characters’ lives. And our last glimpse of Hae Sung, in the final seconds of “Past Lives,” is through the window of a car taxiing him to the airport — the film’s final farewell.

Eventually, Song lets us get to know Nora, Hae Sung, and Arthur, but on her terms and in her way. Like the transparent boundaries she creates around her characters, she has boundaries too, some figurative but many literal. She decides how close we’re allowed to get to Nora and, by extension, herself, alternating traditional close-ups with compositions that distance us. Song constantly uses frames within frames, characters positioned inside doorways, train windows, house windows, car windows, hotel windows, phone windows, and computer windows. When we see Nora and Hae Sung’s hands holding a metal beam on a train for support, their hands are nearly overlapping, almost primed to consummate their meeting with an extramarital holding of hands. We see it through another train car’s window; we meet Arthur for the first time through the window of an artist residency. When Hae Sung asks Nora to visit him in Seoul, and they mutually realize it won’t work, the camera rests on a window looking outside as day turns to night, setting the sun on their hopes for a relationship. Inside Nora and Athur’s apartment, Song sometimes frames their bedroom cuddles and pillow talk through the door’s wide windows, returning us to the point of view of the opening scene — as a voyeur, a guest in these characters’ lives. And our last glimpse of Hae Sung, in the final seconds of “Past Lives,” is through the window of a car taxiing him to the airport — the film’s final farewell.

I wanted to organize this piece around Song’s matrix of visual symbols, breaking them down through a few categories, like “airports, boats, cars” or “restaurants, bars, libraries.” I found it an impossible task; Song’s transitory spaces aren’t just those that bring bodies from one place to another; they are porous, leaking through time and memory. This begins with a few delicate split-second flashbacks––the flashes of reminiscence to Nora and Hae Sung as kids when they first meet in a New York City park or a glimpse of the bifurcated street from childhood that signified their separate paths in this life. I say “this life” because, as “Past Lives” ends, Hae Sung invokes the Korean concept of “In-Yun,” the idea that either signifies how relationships are cosmically fated over 8,000 lifetimes of chanced interaction or maybe just that the person who mentions it wants to get laid. For Hae Sung, it’s probably both, as he longingly tells Nora he’ll catch her in their next life cycle, adding another layer of life to their 8,000. “Past Lives” begins with children catching the sparks of early love and ends not with death but a recognition of our mortality. This signals that each life and each moment is just the past tense for some future self in this life or the next, infusing each meeting with “In-Yun” or maybe just remembrances to come. By revealing “Past Lives” as a kind of extended flashback for the possible “future lives” of Nora, Hae Sung, and Arthur, with bookends between past and future, the film becomes the ultimate liminal space as a life between lives, a space between spaces, or maybe just between childhood and old age. In a post-film Q&A, I wasn’t surprised to hear that Song has a degree in philosophy and an MFA in playwriting. She wields the heady rigor of a philosopher with the grace of a narrative artist, expressing complex, deeply melancholic, time-warping notions of our reality and how our lives are lived through the understated elegance of visual poetry, using every location, shape, curve, or window as a new stanza. There are not many movies that rewire how I experience time and my place in it, but proudly, “Past Lives” is one of them.

“Past Lives” begins with children catching the sparks of early love and ends not with death but a recognition of our mortality. This signals that each life and each moment is just the past tense for some future self in this life or the next, infusing each meeting with “In-Yun” or maybe just remembrances to come. By revealing “Past Lives” as a kind of extended flashback for the possible “future lives” of Nora, Hae Sung, and Arthur, with bookends between past and future, the film becomes the ultimate liminal space as a life between lives, a space between spaces, or maybe just between childhood and old age. In a post-film Q&A, I wasn’t surprised to hear that Song has a degree in philosophy and an MFA in playwriting. She wields the heady rigor of a philosopher with the grace of a narrative artist, expressing complex, deeply melancholic, time-warping notions of our reality and how our lives are lived through the understated elegance of visual poetry, using every location, shape, curve, or window as a new stanza. There are not many movies that rewire how I experience time and my place in it, but proudly, “Past Lives” is one of them.